John Phillips

SMARTPHONES!! please click on the picture to REDUCE the SIZE of the pictures

John Phillips

(°1953, Chicago, USA)

Tant pis, Monsieur Doo-champ!

Doin’ the Do with John Phillips

(0r vice versa)

by Kathryn Hixson

If I were a shopping center

I’d sure be embarrassed,

I know I’d never get a date…

with some cute little building,

like from Paris.

– Jonathan Richman

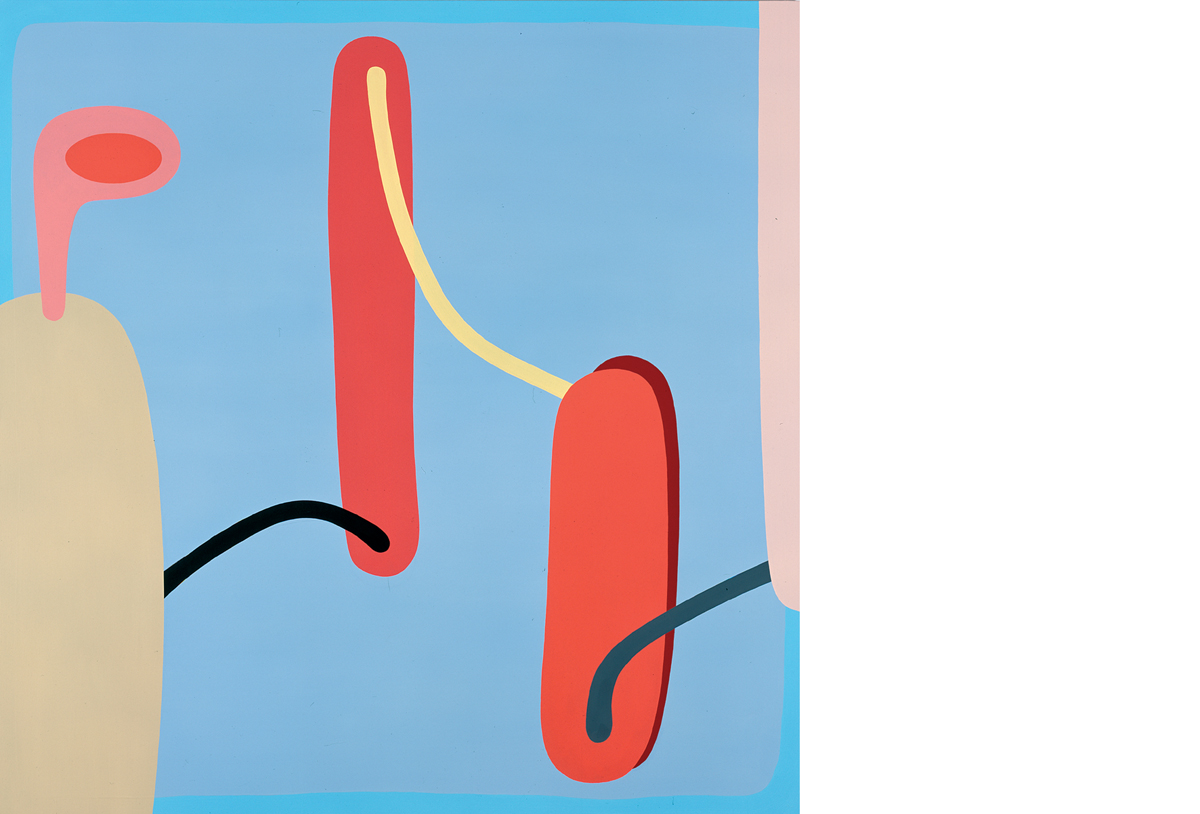

John Phillips has remarked that if Barnett Newman had owned a lava lamp, it might have looked like one of his own paintings. Indeed, Phillips’s inimical mix of serious-minded abstraction and eye-hugging visual entertainment does seem to borrow equally from these vastly different arenas. Throughout his extensive body of work, there is a certain inevitability in his brilliant fields of color populated by skillfully composed, astutely drawn figures. The seem as “natural” as the shopping mall mentioned above,

but like in Richman’s personification, they aspire to better company than usually expected: they can pass for a more upscale company, more like those pictures from Paris.

Like many in his generation coming of age in the mid-1970s, Phillips was jolted out of aesthetic lassitude by slides of Picasso’s Demoiselles D’Avignon and blood-curdling tales of bourgeois shock at Marcel Duchamp’s Urinal. From the vicissitudes of hippie psychedelia and transcendental Ansel Adams landscapes, in college in Colorado Phillips jumped onto the almighty Grid of Abstraction, absorbing the rules of Mondrian, Albers,

Hans Hoffman. Frank Stella had said of his moment after AbEx, “Painters could do anything, you just had to do it.” Phillips had to struggle to find a way past this master, jumping around that holy space of figure and ground already populated by Elizabeth Murray, Larry Poons, and Al Held.

With Greenbergian fever still hanging heavy in the air, painters were hungry to find that perfect picture plane, though conceptualism and feminism were punching up the problems of the good fight. Phillips had the opportunity to attend the Whitney Independent Program in 1978,

which, if nothing else, managed to saturate his young mind with a glut of art-world dilemmas.

Even in those early days, Phillips would grab onto the rules of the game, while seriously undermining their claims for any transcendental truth.

An early canvas titled Humbert’s Dilemma from 1979 is a case in point.

By this time Phillips was composing abstract painting derived from conceptual rules, using geometry and set theory, to predetermine the aesthetic outcome. This very large painting is populated by overlapping sections of squares and circles marching to the rigor of the grid.

However, on closer inspection, the specificity of each shape – its hue, technique, shape, and placement, — causes a raucous dance rather than a staid pictorial analysis. By referring to Vladimir Nabakov’s notorious lecher in the title, Phillips sets up a dichotomy which continues to drive his work today: Which is better? To save the myth of purity (the young voluptuous Lolita/ young painting) and the stolidness of moral rules (salvaging her chastity and the honor of the Grid), or to succumb to the rapt pleasure of physical connection (of sex and/or painting), indulging in “the ol’ in and out” of the picture plane? The answer, of course, lies on that picture plane.

As much as Phillips subscribed wholeheartedly to non referential abstraction, the artist was also drawn to the perverse fun of Marcel Duchamp, with his weird sexual innuendoes buried in highly personal symbology. But Phillips didn’t seem to get down with the punster’s rejection of the “retinal.” Ditto the hard-core conceptual work of Mel Bochner and Bruce Nauman: Phillips appreciated the gesture, but kept hold of his painterly bag of tricks. So, throughout the early to mid 1990s,

he continued to make abstractions that broke all the rules. But even as he made shaped canvasses, multiple panels pieces, used nostalgic 1950s designs, or choose particularly brutal color schemes, each strategy seemed to reinforce abstraction’s rules by insouciantly ignoring them.

Get down tonight

As Phillips navigated through painting’s treacherous waters,

he simultaneously sunk onto the beer-soaked, noxious depths of rock and roll. If abstraction freed the mind, then punk rock freed the body.

Typically, Phillips dove head first, was fully committed to the music scene then was out of it by 1979, becoming a deejay provocateur and prodigious record collector concentrating exclusively on African American music of the 20th century. It is dangerous to align any artist’s various pursuits, the bad-boy sensuality of early R&B all the way through to late 70’s sleaze-punk can be traced as easily in Phillips’s 5000-odd 45 rpm records as in his painting and drawing from the last 30 years. And beginning in the early